Tourists, even locals of the right persuasion, often invoke the movie Blade Runner when talking about Tokyo. Director Ridley Scott’s 1982 science fiction film is full of evocative images, some of them clearly Japan-inspired, like that of a geisha popping pills on a giant advertising screen above a rain-drenched neon metropolis. Our first introduction to Rick Deckard, the film’s main character, played by Harrison Ford, comes outside a noodle bar, whose elderly counterman beckons him with Japanese greetings, like “Irasshai,” and “Dozo.” But to what extent, really, did Tokyo inspire the look of Blade Runner?

Screencap from Blade Runner (1982), distributed by Warner Bros. Pictures.

On Friday, October 6, 2017, the sequel Blade Runner 2049, starring Ryan Gosling and a much older Harrison Ford, hit theaters in the U.S. Here in Japan, the film was not released until three weeks later, on October 27. Ford, director Denis Villeneuve, and actresses Ana De Armas and Sylvia Hoeks were actually on hand for the premiere at the Roppongi Hills complex in Minato Ward the day before the 2017 Tokyo International Film Festival started.

Since I was screening other films for the festival, it was not until this weekend that I had a chance to see the movie—on a rainy day in Tokyo, no less. Perfect viewing conditions, if you’re someone who associates Blade Runner with Japan’s capital. Since there are many people who do, perhaps there’s no better time to question the film’s true inspirations and talk about the role local legend may have played in identifying Shinjuku, Tokyo, with the movie.

Screencap from Blade Runner (1982), distributed by Warner Bros. Pictures.

Consider the following excerpt from an article posted on Fodor’s Travel the day of the sequel’s U.S. release:

The wall-to-wall neon lights and atmospheric, crowded little alleyways of Tokyo’s Shinjuku municipality are enough to put a Blade Runner fan in mind of any number of the movie’s scenes. It is Shinjuku’s Kabukicho district, however, that is said to have specifically inspired much of Blade Runner’s set design.

The neon lights of Kabukicho, as seen from a pedestrian bridge over Yasukuni Street in Shinjuku.

If you start Googling, you are also likely to come across TripAdvisor reviews and threads on the japan-guide.com Question Forum linking a place in Shinjuku called Omoide Yokocho with Blade Runner. Last year, in an essay on Lens — the photojournalism blog of The New York Times — even Daido Moriyama, the Japanese street photographer, was compelled to say:

When I watch the movie “Blade Runner,” I think of Shinjuku; and when I’m in Shinjuku, I feel like I’m in “Blade Runner.”

Acquired by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1980, Moriyama’s most famous photo (see above) is perhaps Stray Dog, Misawa, Aomori, 1971. This is an image I encountered my first year in Tokyo while browsing the bookshelves in Tower Records Shibuya.

If anyone knows Shinjuku, it is Daido Moriyama. And considering the fact that it has been seven years since I moved to Japan and encountered that image in the bookstore, I have to admit, I did go about tweeting one night in full confidence that I, too, knew parts of Shinjuku like the back of my hand.

Omoide Yokocho, Shinjuku's "Memory Lane," a.k.a. "Piss Alley"

As explained in tweets subsequent to the one embedded above, Omoide Yokocho serves as a narrow portal to Kabukicho, the red-light district east of Shinjuku Station. The generic “Memory Lane” is not its only nickname; it is also less flatteringly known as “Piss Alley.”

As Donald Richie notes in his 1999 book Tokyo: A View of the City, public urination is (or at least was then) still common in Japan, and it even once originated a folk custom whereby men would say, “We are the pissers of Kanto,” as they urinated side-by-side. As the story goes, the former city of Edo, which would later become Tokyo, was born as two warlords, one of them Tokugawa Ieyasu, marked their territory, so to speak, on the battlements of the fallen Odawara Castle.

The entrance to Omoide Yokocho.

Today, tourists prowl Piss Alley, looking for an open stall where they can squeeze in and eat yakitori (grilled chicken skewers) and motsu ni (stewed giblets, a personal favorite of yours truly, whenever The Gaijin Ghost sees fit to haunt Omoide Yokocho).

A vat of motsu ni.

Motsu ni dished out in a bowl.

Yakitori chicken skewers.

Some of those stalls require you to order an alcoholic beverage when sitting down. As you fill up your bladder on beer — and soon realize there’s no restroom in sight — you may start to get a feel for why public urination has, historically speaking, been less taboo in Japan than countries like the U.S., where it is illegal in every state.

But we are getting away from Blade Runner. The point is, Omoide Yokocho itself is rather evocative. The atmosphere is very similar to the one conjured by Blade Runner’s noodle bar. And yes, some of the food stalls here do specialize in noodles, too.

Since Omoide Yokocho does, as mentioned, serve as a portal to the neon playground of Kabukicho, it is easy to see why foreigners, including that “Joshua Meyer” fellow doing the tweeting, would be led to make the Blade Runner comparison. But of course, Tokyo is littered with many such yokocho alleys. Another example is Nonbei Yokocho (“Drunkard’s Alley”) in Shibuya.

Apparently, some of those other yokocho alleys and noodle stands are also identified with Blade Runner. When I posted that tweet a few weeks ago, I soon found myself having a brief Twitter exchange with Carla Norton, New York Times bestselling author of The Edge of Normal. As her Twitter profile states, Norton is a “devoted Japanophile,” which is why The Gaijin Ghost is lucky enough to hold her as a follower (one of few followers, alas, at this juncture).

As you can surmise from the screenshot above, searching online in the interval between the first and second tweet yielded nothing in the way of a primary source that would back up the claim that Shinjuku, Kabukicho, or Omoide Yokocho, specifically, played any part in inspiring Blade Runner.

The New York/Hong Kong Connection

Sources like Off-World: The Blade Runner Wiki and book chapters like this one have repeated the claim that Blade Runner was inspired by Kabukicho. But when you go back and look for a direct quote from Ridley Scott or his production designer, Lawrence G. Paull, what actually turns up are blurbs from Scott talking about New York and Hong Kong. Speaking with The New York Times in 2007, on the occasion of Blade Runner’s 25th anniversary, Scott explained how he designed the world of Blade Runner.

“I was spending a lot of time in New York. The city back then seemed to be dismantling itself. It was marginally out of control. I’d also shot some commercials in Hong Kong. This was before the skyscrapers. The streets seemed medieval. There were 4,000 junks in the harbor, and the harbor was filthy. You wouldn’t want to fall in; you’d never get out alive. I wanted to film ‘Blade Runner’ in Hong Kong, but couldn’t afford to.”

High-rise apartment buildings in Hong Kong, as seen from the upper deck of a tram.

As if that were not enough, a simple perusal of the Wikipedia entry on Blade Runner reveals another quote with a book citation, saying Scott drew from the landscape of “Hong Kong on a very bad day” for the movie. Elsewhere, he has also referenced the idea of “New York on a bad day.” This next excerpt comes from the book Blade Runner by Scott Bukatman:

‘The city we present is overkill. But I always get the impression of New York as being overkill,’ Ridley Scott has said. ‘You go into New York on a bad day and you look around and you feel this place is going to grind to a halt any minute.’ Syd Mead ‘had the Manhattan skyline in mind while creating his original pre-production designs,’ and Scott wanted the Chrysler Building, a superb art deco icon, to figure prominently.

Old scanned photos of Manhattan Island and the Chrysler Building, circa 2000–2001.

Ultimately, the key to understanding where Tokyo fits in as an influence may lie with someone else entirely—not the director, but his concept artist, the aforementioned Syd Mead. In a 2013 interview with Vulture, Mead responded to a question that gets to the heart of what this post wanted to uncover.

There's also a collision of Eastern influences in Blade Runner. Where did you pick up those ideas in order to incorporate them?

My first visit to the Far East was Hong Kong. I was in the army in Okinawa, from '53 to '56, just after the Korean War ended. I admired the sensibilities of the shapes. I went back to Japan in '61. People say I copied the genes of it. The geometric lights and the glowing buildings. The Ginza [District in Tokyo] in '61 was not that active at all. We didn't have pixelated signage. People say, "Mead just copied what's happening." Not true—next time I went over there was in '83, after Blade Runner had come out.

The Wako Department Store building, a central landmark of the Ginza shopping district.

The book On Blade Runner: Four Essays frames it this way:

At some point during pre-production, what was supposed to be a generic city became Los Angeles and a decision was made to go Asian rather than Latino. The resulting look combined elements of Hong Kong and Tokyo in the 1960s, when both cities boasted acres of lively neon but had not yet attained their present levels of opulence.

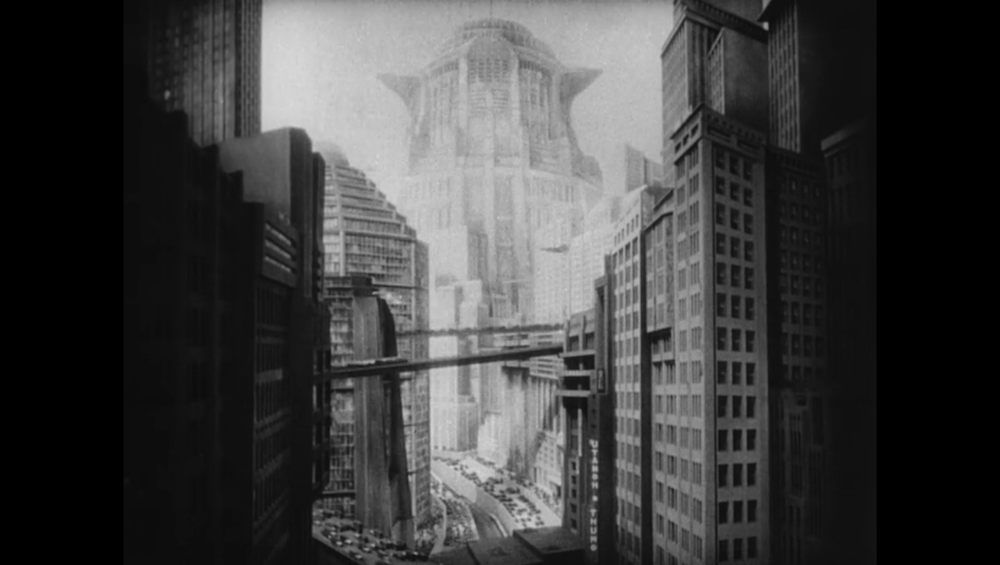

If Mead visited Kabukicho when he came to Tokyo in 1961, it’s possible that the district’s post-war development could have played a part in forming certain images in his mind. But the quotes above would seem to indicate a lack of fixed reference on the part of the filmmakers, who were just as much inspired by things like the Edward Hopper painting Nighthawks and the Fritz Lang film Metropolis when they set about designing the world of Blade Runner.

Nighthawks (1942) by Edward Hopper.

Screencap from Metropolis (1927).

There are other telling quotes. According to special effects supervisor, David Dryer, what led to the image of the huge video advert with the geisha was that Ridley Scott wanted “a bunch of phony oriental commercials where geisha girls are doing unhealthy things.”

The very use of the word “oriental,” an outmoded racial term, here betrays a certain ignorance, for lack of a better word. At other times, Scott has shown a cavalier, almost imperialistic attitude toward non-white cultures. His critically panned Exodus: Gods of Egypt, for instance, was the subject of much whitewashing controversy, yet he defended his decision to cast Caucasians as Egyptians, saying, “I can’t mount a film of this budget, where I have to rely on tax rebates in Spain, and say that my lead actor is Mohammad so-and-so from such-and-such.”

However unconsciously, some of that imperialistic ignorance may be shared by Western tourists making their own first pilgrimage to “the Far East,” as Mead put it. (I include myself circa 2010 in that bunch). These same tourists might not have an eye for the difference between Chinese and Japanese writing. And so to them, Hong Kong and Tokyo might look very much the same, like different colored reflections of Blade Runner.

Japanese poster for Blade Runner 2049, distributed internationally by Sony Pictures.

Blade Runner's Los Angeles, Seen as Every City

In the end, it seems clear that no one city inspired Blade Runner in whole. The look of the film is a hodgepodge of different places, which came about as the result of a collaboration between artists with different travel backgrounds and different frames of visual reference. Other sources have even name-checked cities like Mexico City and Calcutta as visual references, with Mead again pointing to his time as a foreigner in Ginza, here in Tokyo. In Yellow Future: Oriental Style in Hollywood Cinema, he is quoted as saying:

There is a kind of Hong Kong or Calcutta density that Ridley was after. The graphics on the street contribute to that density without being as distracting as English language signs would be for an American audience ... I had noticed that myself in Tokyo on the Ginza where the signs look incredibly jumbled, but I was not distracted by being able to read them so I could enjoy the pure visual composite they created.

Suffice it to say, this very illiteracy, the inability to simply read the signs and tell the difference between Chinese, Japanese, or even Korean, may have been a factor in forming certain impressions among Westerners about Asian cities. (Again, I include myself circa 2010 in that bunch, and even now I’m still illiterate when it comes to Japanese.) Amid the neon hieroglyphics, it would be easy to latch onto the film as a kind of all-purpose touchstone for Eastern exoticism, and say, “Looks like Blade Runner,” even if you were in the wrong city.

Image via Collider.

Image via @BladeRunnerMovieJP on Facebook.

While Chinese writing and Japanese writing do share the same roots and there is some significant overlap where kanji is concerned, Japanese also makes use of hiragana and katakana, two different sets of characters not found in Chinese. One is curvy, the other is simple and straight, unlike Chinese characters, which run more complex. With enough exposure to the two calligraphy styles, Chinese and Japanese, the mind begins to form a general sense of the differences, and it becomes easier to spot those differences—in a movie poster, for example. A visiting Westerner, awash in the neon lights of an Asian city for the first time, might not have the discernment for that, however. It brings to mind what British author G.K. Chesterton said about the lights of Broadway:

“What a glorious garden of wonder this would be for anyone who was lucky enough to be unable to read.”

Ichibangai (First Avenue) in Kabukicho.

None of this is being said to impugn tourists, or detract from anyone’s “claim” on Blade Runner, as it were. Incidentally, Ginza is awfully close to Yurakucho, which may lend credence to Norton’s idea of a “noodle stand by Yurakucho Station, during the rainy season” as inspiration. Here is the full quote she gave explaining that association.

“The movie reminded me of a tiny noodle stand I came across one night during the rainy season. It was about midnight and customers were slurping down a quick meal before catching the last train. I tried to find it when I was in Japan last year, but couldn’t.”

Maybe Ridley Scott’s vision of Los Angeles 2019 is like Christopher Nolan’s vision of Gotham City, in that it can be seen as any and every city: New York, Los Angeles, Tokyo, Hong Kong, and others, all rolled into one vivid amalgamation. After all, Blade Runner was a noted influence on Batman Begins. Yet for The Dark Knight, Nolan turned Gotham City into Chicago. And for The Dark Knight Rises, he turned it into New York.

After Blade Runner, Scott would, of course, go on to direct the film Black Rain, and for that film he did come to Japan and shoot in Osaka. Maybe that is where some of these local legends grew up: in the confusion between films. Though it lacks citation, the Wikipedia entry on Black Rain does in fact state:

The original intention of Ridley Scott was to film in the Kabukicho nightlife district of Shinjuku, Tokyo. However, the Osaka authorities were more receptive towards film permits so the similarly futuristic neon-infused Dotonbori in Namba was chosen as the principal filming location in Japan.

In the absence of any firm supporting evidence on the part of a Blade Runner/Kabukicho connection, it seems all too plausible that memories of Scott’s time in Japan, filming Black Rain, may have been conflated with the Tokyo-esque visual design of Blade Runner to spark a local legend about Omoide Yokocho. Japan tends to be insular, and it is not a stretch to think that some local merchant without much knowledge of the outside movie world might mix up two Hollywood films by the same director with Japanese ties.

Perhaps we cinephiles who are (as it turns out, superficially?) versed in the lore of Japan’s capital have been operating under the wrong impression, and the Kabukicho connection is in fact nothing more than a common misconception, something reverse-engineered from the way Shinjuku at night seems to channel Blade Runner, and vice versa. Either that, or there is some other quote out there from the filmmakers that we have yet to encounter.

If you know of any such quote, you can drop @TheGaijinGhost a line on Twitter. Though an issue like this might be too obscure to warrant it, it would be great if a website like Snopes.com could launch a full investigation that would either validate or definitively debunk the rumor that Blade Runner was in any way inspired by Kabukicho.

In the meantime, Blade Runner 2049 is out in theaters now. And if you are a traveller, you can take a trip down Shinjuku’s “Memory Lane” anytime you visit Tokyo.